By Lars Martinson, Pliant Press, 116 pages

By Lars Martinson, Pliant Press, 116 pages

In his seminal work, Comics and Sequential Art, Will Eisner describes the relationship between illustrator and writer as the fundamental tension in comics. The writer pushes for a more developed story line, meaning more panels and more room for text boxes and speech bubbles. The artist pushes for high quality, beautiful art, meaning more splash pages (full page panels) and more room for artwork. An emphasis on writing leads to a plot driven story, while an emphasis on art leads to an image driven story: the former creates narrative, the latter creates atmosphere.

In the case of comics where the artist and writer are the same person, it’s not unusual to encounter a work with beautiful detail and a well developed story. The only problem is such a work might take a decade to complete.

With this in mind, Tonoharu: Part One by Lars Martinson did not surprise me with it’s brevity (it’s a lean 116 pages, mostly four panel pages) and spaced out volumes (four years later, only two are finished). Priced above your standard short-form, serial novel entry, it’s tempting to criticize the author for stiffing the reader out of story content.

In what is promised as a four-part series, part one introduces us to the life of an Assistant English Teacher in rural Japan: a mostly brainless and thankless position where the only real challenge is avoiding the crippling isolation of being the sole Anglophone in a foreign country with no companionship or understanding of the culture. This is a position on which Martinson can speak authoritatively, having lived the experiences of his protagonists (however, it should be noted he claims on his blog “This is the most fictional comic I’ve written in years”).

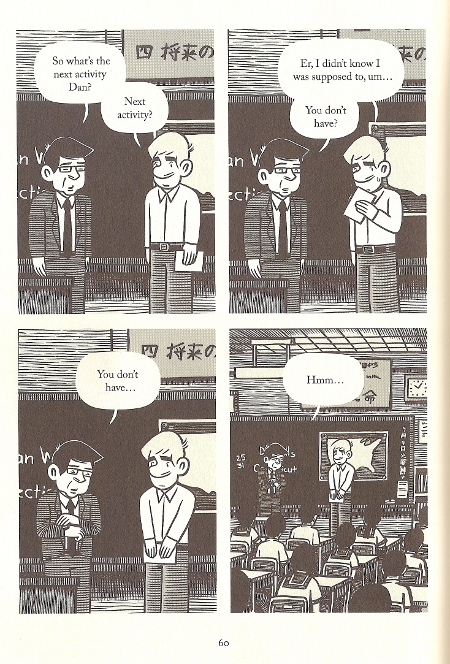

The narrative is divided into three parts (including a prologue that introduces us to a narrator–the successor of the protagonist in parts one and two of the first volume–who abruptly vanishes). There are long conversations that span pages and pages, pausing only to depict awkward silences that follow awkward conversations. While a few scenes drag on punishingly (especially an encounter between protagonist Dan and a mysterious group of European ex-pats living in a Buddhist monastery), I suppose I can give this volume the benefit of the doubt as “part one” of any series is saddled with the double burden of providing an entertaining story while finding a way to develop characters for subsequent entries.

The artwork is beautiful and full of intricate cross hatching. It reminds me of a woodcut (an art form that the Japanese mastered), and at times threatens to make the frames too busy; the relief comes from cartoony people who seem too squat for their environment. The white space in their faces and the molded, dome-like manga hair (which reminded me of my Mii as I read) provide the counterpoint to their painstakingly hatched clothing. This contrast of figure and ground produces, for me, an image of likable characters in a harsh environment, something which perhaps (for westerners) builds some pathos for the hapless Dan, whose sluggish disposition and lack of effort to grasp the Japanese language and culture fuel his sense of alienation. The mix of slacker and “fish out of water” tropes are combined brilliantly at times by Martinson, who creates a universe of uncomfortable situations for his character to traverse (one which teachers will be familiar with is depicted above).

Does art triumph over story? It seems premature to judge, and I feel compelled to read the next volume before I pass judgement in that respect. After a rereading, I find that the atmosphere Martinson creates in this first part lingers and that I am looking forward to exploring this (limited) universe further.

AV Club: B-

Amazon: 4/5 Stars

Me: B+