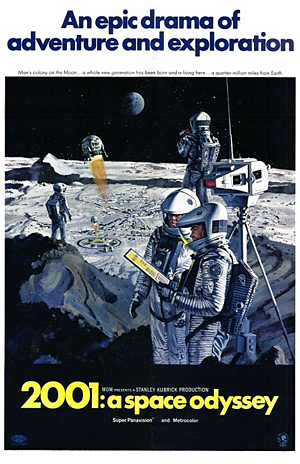

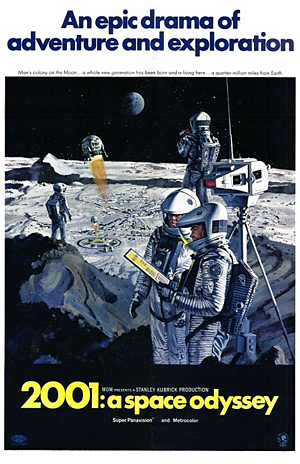

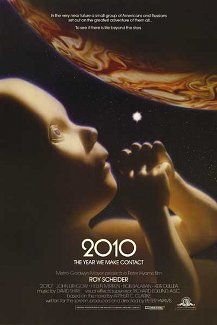

In my science fiction course this summer, we watched Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) after reading the novel of the same title by Arthur C. Clarke. We also read excerpts from the fairly decent The Making of 2001: A Space Odyssey edited by Stephanie Schwam (2000). After that, I decided to take another look at the long anticipated filmed sequel of Clarke’s second entry in his tetralogy, 2010: The Year We Make Contact (1984), which was available on Netflix Instant. The former film is a painstakingly produced, enduring exercise in new-wave sci-fi minimalism which touches the very quick of one’s soul and excites the imagination, while the later film is a concession to commercialism that portends the coming domination of the lowest common denominator in filmmaking.

The recent release of Ridley Scott’s Prometheus has sharply divided critics and people I have talked to along the lines of hard sci-fi (plot/action driven, technically detailed) and soft sci-fi (introspective and pseudoscientific). In her recent review, A.V. Club film critic Tasha Robinson compared Prometheus to Solaris (1972[?]2002), both versions of which rank high on the relative scale of introspection and existentialism. I thought I would challenge why introspective (or “new wave”) science fiction has drawn such criticism by examining the case study of 2001 and its much maligned sequel.

In 1964, Clarke and Kubrick teamed up to produce a film based on one of Clarke’s short stories (“The Sentinel”) which would be a “Journey Beyond the Stars” (an early title of the film). As Clarke notes, many poor films were written at first as screenplays, and many awful novels were written as “novelizations” of films, thus both collaborators decided to flesh out the story as a full-fledged novel while simultaneously creating the film; this was beyond ballsy given their early projections of going from practically nothing to a finished novel and feature-length motion picture released simultaneously in only two years. In a comfort to those tackling impossible projects, two of the greatest writers actually worked for four years, and they would finish barely one year before the first lunar landing in 1969, an event which would define in real life whether their film would come across as futuristic and timeless or dated and hokey compared to real astronautical technology.

In 1964, Clarke and Kubrick teamed up to produce a film based on one of Clarke’s short stories (“The Sentinel”) which would be a “Journey Beyond the Stars” (an early title of the film). As Clarke notes, many poor films were written at first as screenplays, and many awful novels were written as “novelizations” of films, thus both collaborators decided to flesh out the story as a full-fledged novel while simultaneously creating the film; this was beyond ballsy given their early projections of going from practically nothing to a finished novel and feature-length motion picture released simultaneously in only two years. In a comfort to those tackling impossible projects, two of the greatest writers actually worked for four years, and they would finish barely one year before the first lunar landing in 1969, an event which would define in real life whether their film would come across as futuristic and timeless or dated and hokey compared to real astronautical technology.

As Clarke churned out the novel, Kubrick enlisted a virtual army to begin set and model construction for the film. An oft-cited example of the frenetic pace of production: Clarke would often write chapters and present them to Kubrick, who would revise and film scenes, whereby Clarke would view the rushes (rapidly developed film) from a day’s filming and alter the novel accordingly.

In terms of vision, the two were not totally dissimilar, but both had separate agendas. Clarke’s characters in the novel are thinking creatures of emotion in a universe of wonder, while Kubrick sought to portray sterile and emotionless characters in a world of strangeness punctuated by moments of sheer terror. It was ultimately Kubrick who unintentionally got the jump on Clarke, whose novel was released a couple months after the film and was, much to Clarke’s chagrin, sometimes confused for a “novelization.”

I tried my best to explain to my students that comparing the novel and film is akin to apples and oranges, but without a full film curriculum possible (the course was a mere six weeks to explore all of sci-fi) the message was sure to fail. In any case, there is much to be learned by reading the novel and watching the film in succession, including a whole host of illuminations regarding the plot that are otherwise inaccessible to most casual film watchers.

The film itself is a technical masterwork, showcasing attention to detail and visual effects craftsmanship that are unparalleled in any period piece and still hold up far better today than many CGI visual effects produced three or more decades later. As mentioned above, Kubrick had specialists including draftsmen, architects, aerospace engineers, and consultants who were involved in the fabrication of NASA’s period technology all working on building the Discovery, the monolith, and other set pieces. Additionally, he and Clarke poured over the latest technical publications. As a result of his efforts, Kubrick was presented with an Academy Award for Best Visual Effects. Sweeping camera shots paired with the masterful manipulation of the models, such as the docking of the the earth shuttle with the international space station, all set to Strauss’ Blue Danube, are still beautiful and breathtaking to this day.

Kubrick was obsessed with producing a film which was not immediately dated by technological advancements of the very near future. With the spectacular technological and logistical feat of the lunar landing looming on the horizon, such a rapid deprecation of the film’s technology was a very real possibility.

Simultaneously, Kubrick was paradoxically adamant that the film not be considered a prediction, but rather a fable, and be interpreted as such. The clash of a hard science fiction masterpiece in Clarke’s novel, which contains a prescient level of technical detail about space travel, and Kubrick’s stripped-down film, which offers very little in the way of technical exposition, tethers the two works together in provocative and oftentimes frustrating ways: the novel reader can recognize the subtly silent exposition of the scenes, while the period audience and many critics were able only to gawk at spectacular visuals as their Dionysian drive for plot acquisition is inhumanely stifled by Kubrick’s minimalist aesthetic.

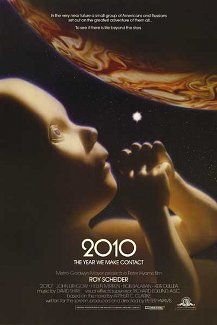

By contrast, 2010: The Year We Make Contact looks laughably dated in the 1980’s. The mod and futuristic set design and spectacular visual effects afforded by the painstakingly constructed models in 2001 are long gone, replaced by cheap looking reproductions and technology which looks very much lifted out of War Games (no disrespect). While the plot picks up somewhat near the original, the film is very much dependent on typical cliches. Roy Scheider as Dr. Floyd from the first failed mission has to team up with the hated Soviets to recover the Discovery before it drops out of orbit into Jupiter. The film lazily borrows the score from Kubrick’s film, inserting clipped segments of Strauss’ Also sprach Zarathustra which was used to such stunning effect in the first film as merely an abbreviated leitmotif for the appearance of the monolith. Additionally, the film leans on the crutch of voiceover, with Scheider reading one-sided letters home to his wife which update the plot action on the mission to Jupiter. In short, it replaces Kubrick’s visionary aesthetic with a more crowd-pleasing, action-oriented plot.

By contrast, 2010: The Year We Make Contact looks laughably dated in the 1980’s. The mod and futuristic set design and spectacular visual effects afforded by the painstakingly constructed models in 2001 are long gone, replaced by cheap looking reproductions and technology which looks very much lifted out of War Games (no disrespect). While the plot picks up somewhat near the original, the film is very much dependent on typical cliches. Roy Scheider as Dr. Floyd from the first failed mission has to team up with the hated Soviets to recover the Discovery before it drops out of orbit into Jupiter. The film lazily borrows the score from Kubrick’s film, inserting clipped segments of Strauss’ Also sprach Zarathustra which was used to such stunning effect in the first film as merely an abbreviated leitmotif for the appearance of the monolith. Additionally, the film leans on the crutch of voiceover, with Scheider reading one-sided letters home to his wife which update the plot action on the mission to Jupiter. In short, it replaces Kubrick’s visionary aesthetic with a more crowd-pleasing, action-oriented plot.

As with most science fiction that we are used to seeing, there is light introspection coupled with an apparent lack of technical detail. While Kubrick gives us a visual essay on how space travel might work based on Clarke’s detailed writings and research, 2010 gives us just enough explanation to gloss over the extant problems so that the filmmakers can progress the meandering plot. There are incoherent details presented, such as squeeze-bottle liquid containers which would make perfect sense in a zero-G atmosphere, but make no sense when the characters are firmly planted on the ground. Come to think of it, it’s not clear how the gravity works on the Soviet spaceship. Additionally, HAL, an integral and complex character from the first film, is spoken to much like a child (or dog) in this film, and is seen only as an obstacle which must be traversed to escape the impending danger at the end of the plot line.

The most satisfying part of 2010 comes when Bowman’s character from the first film reappears to deliver a message from the non-corporeal star beings and warn the American crew marooned on the Discovery of their dangerous position near Jupiter which (SPOILER) will become a second sun in the now binary Sol system, with all of Jupiter’s moons now (possibly?) habitable for human life (I haven’t read the second book).

As Bowman delivers his information, he transitions through the various life stages we originally saw in the final act of 2001. He walks the deck of his former ship, and even converses with HAL, apparently more serene than his last embittered encounter. Having transcended corporeal existence, he can now understand HAL’s actions and even, possibly, forgive him (if such emotions are even in the purview of his new existence). It’s hard to say whether I appreciated this portion of the film as a part of 2010 or as a satisfying resolution to the enmity which defined their parting in 2001, though I feel the later is probably much more likely.

Recently, I’ve been thinking about how sequels (or prequels) are a difficult matter to negotiate, and the difficulty grows proportionately with the gap in years between installments as film technologies and cultural zeitgeist (co-)evolve. While 2010 is not a “bad” film, it is hard to read both films as related other than the common characters and plot elements. In the ways that really matter, they couldn’t be further apart.

In 1964, Clarke and Kubrick teamed up to produce a film based on one of Clarke’s short stories (“The Sentinel”) which would be a “Journey Beyond the Stars” (an early title of the film). As Clarke notes, many poor films were written at first as screenplays, and many awful novels were written as “novelizations” of films, thus both collaborators decided to flesh out the story as a full-fledged novel while simultaneously creating the film; this was beyond ballsy given their early projections of going from practically nothing to a finished novel and feature-length motion picture released simultaneously in only two years. In a comfort to those tackling impossible projects, two of the greatest writers actually worked for four years, and they would finish barely one year before the first lunar landing in 1969, an event which would define in real life whether their film would come across as futuristic and timeless or dated and hokey compared to real astronautical technology.

In 1964, Clarke and Kubrick teamed up to produce a film based on one of Clarke’s short stories (“The Sentinel”) which would be a “Journey Beyond the Stars” (an early title of the film). As Clarke notes, many poor films were written at first as screenplays, and many awful novels were written as “novelizations” of films, thus both collaborators decided to flesh out the story as a full-fledged novel while simultaneously creating the film; this was beyond ballsy given their early projections of going from practically nothing to a finished novel and feature-length motion picture released simultaneously in only two years. In a comfort to those tackling impossible projects, two of the greatest writers actually worked for four years, and they would finish barely one year before the first lunar landing in 1969, an event which would define in real life whether their film would come across as futuristic and timeless or dated and hokey compared to real astronautical technology. By contrast, 2010: The Year We Make Contact looks laughably dated in the 1980’s. The mod and futuristic set design and spectacular visual effects afforded by the painstakingly constructed models in 2001 are long gone, replaced by cheap looking reproductions and technology which looks very much lifted out of War Games (no disrespect). While the plot picks up somewhat near the original, the film is very much dependent on typical cliches. Roy Scheider as Dr. Floyd from the first failed mission has to team up with the hated Soviets to recover the Discovery before it drops out of orbit into Jupiter. The film lazily borrows the score from Kubrick’s film, inserting clipped segments of Strauss’ Also sprach Zarathustra which was used to such stunning effect in the first film as merely an abbreviated leitmotif for the appearance of the monolith. Additionally, the film leans on the crutch of voiceover, with Scheider reading one-sided letters home to his wife which update the plot action on the mission to Jupiter. In short, it replaces Kubrick’s visionary aesthetic with a more crowd-pleasing, action-oriented plot.

By contrast, 2010: The Year We Make Contact looks laughably dated in the 1980’s. The mod and futuristic set design and spectacular visual effects afforded by the painstakingly constructed models in 2001 are long gone, replaced by cheap looking reproductions and technology which looks very much lifted out of War Games (no disrespect). While the plot picks up somewhat near the original, the film is very much dependent on typical cliches. Roy Scheider as Dr. Floyd from the first failed mission has to team up with the hated Soviets to recover the Discovery before it drops out of orbit into Jupiter. The film lazily borrows the score from Kubrick’s film, inserting clipped segments of Strauss’ Also sprach Zarathustra which was used to such stunning effect in the first film as merely an abbreviated leitmotif for the appearance of the monolith. Additionally, the film leans on the crutch of voiceover, with Scheider reading one-sided letters home to his wife which update the plot action on the mission to Jupiter. In short, it replaces Kubrick’s visionary aesthetic with a more crowd-pleasing, action-oriented plot.