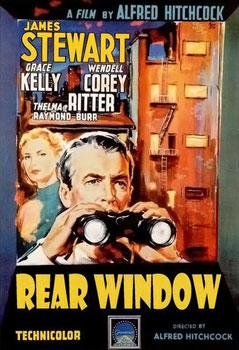

Rear Window (1954)

Dir. Alfred Hitchcock, 112 min., DVD

Watching Hitchcock’s films might be considered by some a master class in pacing and suspense, but for my money it’s a dead ringer for the difference in how writers and directors delivered a story now and fifty years ago. There are not many films of comparable pacing that I have watched from the last ten years of cinema that hold so much for the end, except perhaps the works of Christopher Nolan.

Watching Hitchcock’s films might be considered by some a master class in pacing and suspense, but for my money it’s a dead ringer for the difference in how writers and directors delivered a story now and fifty years ago. There are not many films of comparable pacing that I have watched from the last ten years of cinema that hold so much for the end, except perhaps the works of Christopher Nolan.

The film, by all contemporary standards, proceeds at a glacial pace, and if I take that metaphor to an annoying level, the glacier of pacing is slowly melted away by the heat of action (boo, boo, terrible!!!). Garbage metaphors aside, the heat does figure prominently as noted on a recent episode of Filmspotting, playing a pivotal role in the main action of the film (the peeping of the protagonist into open windows).

Jeffires (James Stewart), an injured photographer who is confined to a wheelchair during his convalescence, is visited accordingly in day and night by his nurse Stella (Thelma Ritter) and romantic interest Lisa (the stunning Grace Kelly). The film works equally well as a thriller and a class study, with Jeffries peering into illicit behavior and peoples’ personal class afflictions in equal measure. Jeffries avoids marriage to Lisa (in what Adam Kempenaar calls the most unbelievable bit of acting ever) on account of her “Fifth Avenue” lifestyle being incongruous with his various rugged, masculine photography assignments. Jeffries early on notices unusual behavior from one of his neighbors which prompts him to bring in his police detective friend Doyle (Wendell Corey), an antagonist for the speculative trio of Jeffries, Stella, and Lisa.

Through twists and turns, the murder is both proven and disproven through vivid imaginary crime reconstructions by the trio (reminiscent of the climax of a Sherlock Holmes novel) and the deflating detective work of Doyle. Perhaps the most arresting theory behind the film is that of surveillance, and what it does or doesn’t tell us about people. Seeing actions disconnected from context and without explanation offers a glimpse of private life that goes beyond suspicion or blind speculation, yet is no more factual or truthful than either. On a meta-level, it comments on the film viewer’s voyeuristic tendencies, the watching of someone who is incapable of watching you. The exquisite tension that lingers with me is the peril of unobserved observation, that the object may turn his gaze on you, shattering the barrier that makes surveillance a passive activity–much like an actor breaking the fourth wall. A brilliant and elemental foundation for a plot.

The slow, slow pacing is alleviated by the masterful set in which the entire action of the film takes place. Apart from a single room in Jeffries’ aparment, the entire setting of the film is the view through the vibrant courtyard and alleyways that provide access for the protagonist and viewer to the unsanctioned glimpses into open windows. It functions as a self-contained universe of intrigue and interaction: a microcosm of a metropolis housing a multitude of sin, intrigue, and suspicious imagination.

A-

Beauty and the Beast (1991)

Dirs. Gary Trousdale & Kirk Wise, 84 min., on the Disney channel (of all places)

I have a certain fascination with films for children, in that they must both entertain the child as well as not be abhorrent to the adult paying for and accompanying said child to the movie theater. In addition, they must be entertaining to children ranging from 3 to 12 years old, a range marked by radically different interests and cognitive levels. If a film rises to the pick of the litter (in 101 Dalmations parlance), it is rewatchable by the adult for nostalgia and enjoyment purposes for many years after the initial viewing, and may be imparted on a subsequent generation.

I was watching the film Tangled with my niece the other day and I noticed that computer animation is a totally different experience from the hand drawn animation of my childhood: the lines are crisp and clean, voices are perfectly matched, scenes are crisp and bright and almost bursting with color. But there was definitely something unsatisfying about the film.

I’m the very last person to say everything old is good, everything new, bad. But there are some substantial changes which are worth noting.

Beauty and the Beast was the forerunner of future animated films with the first in-company use of a computer animation sequence in a feature film (the scene where Belle dances with the Beast in the ballroom). In a film where there are tens of thousands of expertly hand drawn cells animated into a feature by what was, at the time, one of the most expert production crews in the animation business, the computer animation looks shoehorned and does not fit the aesthetic of the film. By today’s computer animation standards, the product is quaint and is reminiscent of a scene from the early computer game Rift.

Nevertheless, this embodies the spirit of the zenith of Disney hand-drawn animation that included The Little Mermaid (1989), The Rescuers Down Under (1990), Beauty and the Beast (1991), Aladdin (1992), and The Lion King (1994). These films also represent the run up to a fully computer animated film, with each film incorporating more sophisticated computer-aided animation techniques.

The film also represents a golden era of sorts that contains conventions that current films abandon. For the most part, the actors in this film are Broadway voice actors, the most notable exceptions being Angela Lansbury and Jerry Orbach (whose French accent makes his grumbly Dirty Dancing and Law and Order personas unrecognizable by comparison). The songs are practically written for a Broadway musical, and one might call this an animated musical rather than an animated feature since the songs take such precedence. According to IMDB trivia, Lansbury suggested that the title track be sung by a professional singer, but she recorded one take to appease the production staff, and that take was ultimately used in the film. By comparison with computer animation, there’s something charming about the slapdashedness of such a gargantuan project as drawing and animating tens of thousands of still frames combined with rock and roll snap takes.

Pixar films are clinical in their mechanized precision, and do not have run-over coloration in the stills, mismatched voice and character movement, or reused animation: flaws that endear an audience. Outtakes are manufactured, but are the simulacra of imperfection. The voices are supplied by Hollywood stars who most likely record several hundred, heavily-edited takes: as Jon DiMaggio (Bender from Futurama) pointed out in his interview with AV Club, they are brought on cast to sell tickets with their names, not give quality performances. Beauty and the Beast is a nostalgic trip back to before the tipping point where animation became a fully computerized and (comically) further commercialized art form.

B+