Pearl Jam and Nirvana go hand in hand in my book: while both bands channeled the disaffected and damaged psyche of 1990’s youth, Pearl Jam’s (relatively) bright guitar sounds and Eddie Vedder’s melodic falsetto sharply contrasted with Nivana’s banged-out, distorted guitars mixed with Kurt Kobain’s raspy shriek. Both vocalists were power rockers and controlling presences in their bands, but my take on their approaches was that Pearl Jam was really holding onto pop power ballads in their earlier work where Nirvana seemed to hit you with an assault of feedback, lending more to a “What the f**k did I just hear?” experience than the more reserved and conventional Pearl Jam albums.

Pearl Jam and Nirvana go hand in hand in my book: while both bands channeled the disaffected and damaged psyche of 1990’s youth, Pearl Jam’s (relatively) bright guitar sounds and Eddie Vedder’s melodic falsetto sharply contrasted with Nivana’s banged-out, distorted guitars mixed with Kurt Kobain’s raspy shriek. Both vocalists were power rockers and controlling presences in their bands, but my take on their approaches was that Pearl Jam was really holding onto pop power ballads in their earlier work where Nirvana seemed to hit you with an assault of feedback, lending more to a “What the f**k did I just hear?” experience than the more reserved and conventional Pearl Jam albums.

Interestingly, if you want to reduce that difference to a spectrum, both bands seemed to meet in the middle after their early records. Nirvana and Kobain (perhaps jaded and capitulating to the commerical success of their initial work) seemed to move more towards traditional stadium anthems, with Kobain even speculating just before his death (whether sarcastically or not) that the next Nirvana album would be a pop record. Alternately, Pearl Jam attempted to branch out into more experimental sounds after the death of Kobain and the decline of the first wave of grunge rock (at least, first major-label wave). The stadium rock of Ten (1991) and Vs. (1993) gave way to darker themes and sounds with Vitalogy (1994). The subject matter became more visceral, twisted, and isolated, making their previous attempts at probing the underworld (e.g. “Rats” on Vs. or “Master/Slave” on Ten) look tame by comparison.

Next came the zen koan that was No Code (1996), which came across as Vedder’s spiritual and existential musings. It had a very cabin in the woods / nature boy vibe and failed to produce major singles, leading to relatively “dissapointing” sales of only one million records. In the pre-file sharing era, this spelled a major defeat for a band that was riding high on two straight blockbuster albums. I’ll argue in other posts that all of these albums were great in their own way and that Pearl Jam pulled off the “grand slam” of recordings, debuting with four quality records that stand the test of time.

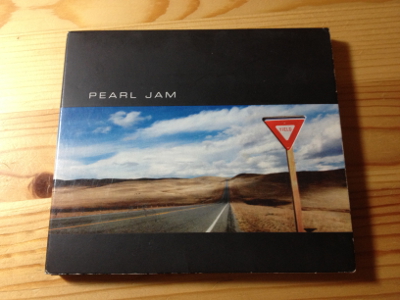

Here I’m going to talk about their return-to-form record, 1998’s Yield. Chasing the early success of the iconoclast Ten, Pearl Jam returned to the stadium anthem format. What I feel differentiates this album from other stadium anthemists that we are plagued with today (e.g. Muse, Coldplay, Mumford and Sons, etc.) is the deeply personal and poetic lyrics that Vedder gives us combined with Mike McCready’s steady, but nuanced guitar work.

By this album, the band seems to have progressed to a much tighter and more layered configuration. Gone are the pompous intros of earlier albums, such as the opening licks to “Alive” or, later, the opening track on Vs. (“Go”) that subjects listeners to a false-start bass guitar solo and some cheesy guitar noodling, followed by the assault of McCreedy pounding out the bridge chords. On No Code, “Brain of J.” opens with a playful, two-second false start, and then McCready immediately launches into his shredding riff, and Vedder hits the ground running with rapid fire vocals that set a quick pace.

All the pacing is dispensed with on the second and third tracks however, almost like the band backs off a bit from that forceful opening volley. After that two-track break, Vedder unleashes his two strongest tracks lyrically: the parable “Given to Fly,” and a form poem, “Wishlist.” In the first, Vedder delivers an uplifting, didactic metaphor of physical transformation as a (hopeful) stand in for a worldwide spiritual awakening: A man who sprouts mythical wings “floated back down cause he wanted to share the keys to the locks on the chains he saw everywhere.” Clearly, the people of that (our) world are not ready, as they repel their winged friend until he becomes only a “strange spot in the sky” joined by the few that are willing and able to take that next step.

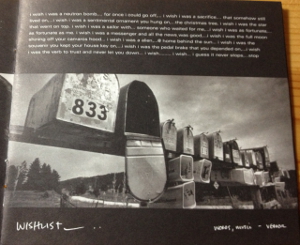

In “Wishlist,” Vedder methodically rattles off a seemingly random sequence of “wishes” that initially sound like pompous writing, but upon closer inspection turn out to be images of perfect moments that the narrator has imagined to satisfy deep emotional longings. Some of them appear to have the heartland signature of Vedder (“I wish I was the full moon shining off a Camaro’s hood”) while others seem to be the desperate longing of a deeply isolated man hoping to feel some personal connection, no matter how insignificant: “I wish I was the souvenir you kept your house keys on.” The track pulses with energy, and it seems like Vedder barely restrains his vocal performance at times. Even the refrains and guitar solo seem restrained, in contrast to, say, the explosive catharsis of tracks like “Jeremy” from Ten.

In “Wishlist,” Vedder methodically rattles off a seemingly random sequence of “wishes” that initially sound like pompous writing, but upon closer inspection turn out to be images of perfect moments that the narrator has imagined to satisfy deep emotional longings. Some of them appear to have the heartland signature of Vedder (“I wish I was the full moon shining off a Camaro’s hood”) while others seem to be the desperate longing of a deeply isolated man hoping to feel some personal connection, no matter how insignificant: “I wish I was the souvenir you kept your house keys on.” The track pulses with energy, and it seems like Vedder barely restrains his vocal performance at times. Even the refrains and guitar solo seem restrained, in contrast to, say, the explosive catharsis of tracks like “Jeremy” from Ten.

That restraint is lifted in “Do The Evolution,” which both decries overabundant consumerism and portends the return to imperialism post 2001 (it also marks the first video since the widely acclaimed “Jeremy” years earlier). Vedder’s vocal performance on this track comes the closest to flying off the rails, with him truly channeling the consumer lust of the narrator by the final verse, screaming, “IT’S EVOLUTION BABY!”

“MFC” is an open-road song where the rhythm section of the band shines, driving the steady beat behind the propulsive guitar work and Vedder’s tightly paced lyrics. Immediately following are the haunting sounds of “Low Light,” which transports the listener to sitting on the hood watching the setting sun after the excitement of “MFC”‘s sprint down the highway.

The more literary “In Hiding” supposedly channels the writings of Charles Bukowski (according to Wikipedia). I didn’t hear the literary allusions on a relisten, and I certainly didn’t appreciate them as a teenager. It’s a serviceable anthem and gives Jeff Ament a chance to deliver a solid bass guitar performance.

“Push me, Pull me” carries on the somewhat regrettable tradition begun on their previous album of including at least one spoken word track. In my opinion, these tracks are the low point of every album, and they always come across as pretentious and unnecessary. Vedder’s poetry is much better served when it is poured into a form, as described above, and when given license to run in free verse sounds too much like amateur hour at the beat poetry lounge.

The album wraps up with “All Those Yesterdays,” not perhaps the strongest finishing track PJ has ever delivered. It builds to a wild guitar run and Vedder’s harmonized voice repeating the titular lyrics, then is followed by the hidden track which is an odd, vaguely Hasidic sounding folk guitar piece. The most positive thing I can say about the hidden track is that its sour-sounding guitar managed to jolt me awake a couple of times when I fell asleep studying for an exam.

Yield houses some of the most recognizable middle-period singles for the band and lofted them back to their previous heyday of a solid alternative radio staple. In terms of inventiveness and cohesion, it doesn’t approach Vitalogy, which I consider to be their masterpiece both lyrically and sonically.

OK, gotcha, next please:

Weezer: Weezer (The Blue Album) (7.31)

Stone Temple Pilots: Core (8.7)

James: Seven (8.14)